In the quiet Chicago neighborhood of Jefferson Park, stands as a monument to the enduring soul of American pool halls. Since 1984, this hall at 4637 N. Milwaukee Avenue has been more than a venue—it’s been a home for hustlers, league champs, and anyone chasing the break.

Spanning 41 tables across three rooms—including seven- and nine-footers—Chris’s draws players of every stripe. The front room features vintage Brunswick tables and Three-Cushion setups, radiating the kind of worn-in charm that’s earned it a cameo in The Color of Money (1986), part of which was filmed here.

It’s dimly lit. Quietly competitive. Reverent of its past. Still, Chris’s continues to evolve, one rack at a time.

Pool has always lived on the edge—occasionally thrust into the spotlight, more often left to flicker in the corners of smoky rooms. Chris’s Billiards sits at the crossroads of that cultural tension.

The sport’s had two big comebacks. First, in 1961, when The Hustler ignited a national boom. Pool halls opened everywhere; in Manhattan alone, over 3,000 operated by the mid-’60s. Then came the fade—cultural shifts, Vietnam, disco, arcades. In 1986, The Color of Money brought it roaring back.

This time, the vibe was glossier. Pool rooms became upscale lounges, courting professionals and distancing themselves from the blue-collar image. But as the ’90s ended, so did the novelty.

A Hard Business to Keep Afloat

Owning and operating a pool room is a challenging business. It’s not just about having the space and tables; it’s about staying afloat amid the constant pressures of overhead costs, changing consumer trends, and shifting cultural attitudes toward the game.

At its peak (around the 1930s–1950s), New York City had over 1,000 dedicated pool halls. Today that number has declined to approximately 69, excluding bars and other venues where pool tables are secondary attractions.

For many pool room owners, one of the primary challenges is space. A pool table requires a lot of room, often more than a standard bar or restaurant. The cost of real estate—especially in urban areas—adds significant pressure. For example, in cities like New York or Los Angeles, rents are astronomical, and to survive, a pool hall must bring in consistent traffic. But most of the revenue comes from players renting tables by the hour. Because pool is often considered a low-barrier, low-cost game for casual players, it’s difficult to generate the kind of revenue needed to support large spaces. This leaves owners with little choice but to adjust their pricing and add amenities like food and drink, though even this is no guarantee of success.

Cue maker Paul Mottey, now owner of Breakers in Pittsburgh, has firsthand experience: “The biggest challenge is space—and rent,” he said, highlighting the financial strain. Similarly, Jim Gottier, former owner of Greenleaf’s Pool Room in Richmond, Virginia, explains it bluntly:

“You need a ton of square footage for these big tables, but you can’t charge much to play. It’s a hard way to make a living.”

Besides the economic realities, there’s the issue of the game’s cultural relevance. In an era where digital entertainment often outpaces physical spaces in popularity, pool rooms struggle to stay relevant, especially with younger generations. Newer generations are more likely to flock to places with video games, modern technology, and social media-integrated experiences. The classic appeal of a pool room—dimly lit, full of the sound of balls clacking, conversations over drinks—is harder to sell in a world of instant, immersive experiences.

This struggle isn’t unique to pool halls in larger cities either. Small-town and rural pool halls face similar battles with foot traffic, not to mention the increasing competition from other entertainment sources—such as bowling alleys, movie theaters, or home gaming systems. And let’s not forget the social challenges, either. Pool halls have long carried a stigma—an association with gambling, rowdiness, and even crime. While many modern pool rooms try to break away from these associations, they still face the uphill challenge of attracting a mainstream crowd.

The economic and cultural struggles culminate in a reality where many pool halls close down, unable to sustain their business model. Even the upscale establishments from the ‘90s that once attracted a more affluent crowd with sleek design and high-end service have shuttered in recent years, unable to keep up with the changing times.

Where Are We Now?

A third wave may be building—driven by streaming, social media, and global tournaments.

British promoter Matchroom has elevated pool’s prestige with polished events like the Mosconi Cup and U.S. Open, offering real prize money and worldwide exposure. The image? Sharper. The play? Tighter. The reach? Bigger than ever.

At the grassroots, junior leagues and barroom tournaments thrive. Women and youth participation is growing. Online coaching and tournament access are just a click away. And old pros like Earl Strickland keep advocating for a clean, competitive future.

Women at the Table

Women have always played—yet rarely gotten their due. Starting out in the world of pool can be especially challenging for amateur women. Walking into a pool hall, many women face an immediate wave of unspoken pressure — assumptions about their skill level, unwanted advice from strangers, or even outright skepticism about their place at the table. Instead of being able to focus solely on improving their game, they often find themselves battling stereotypes that question their seriousness or competitiveness. The simple act of learning how to line up a shot or develop a strategic mindset can feel heavier when done under the watchful, and sometimes critical, eyes of more seasoned players who may not always offer encouragement.

Beyond the social dynamics, there are also fewer formal opportunities for women at the amateur level compared to men. Local tournaments, leagues, and even casual games can feel dominated by male players, creating a sense of isolation. It’s not just about building technical skills like precision and control; it’s also about building the confidence to take up space in a traditionally male-centered environment. For many amateur women, progress in pool is as much about mastering the psychological aspects — staying focused, resilient, and self-assured — as it is about sinking balls into pockets. The journey can be tough, but it also forges a strong sense of pride and community among women who persist and carve out their place on the felt.

Professional player Jeanette Lee, known as The Black Widow, said in a 2018 interview with Billiards Digest, “I was never trying to be the best woman player—I was trying to be the best, period.”

Her dominance and charisma helped introduce millions to competitive women’s pool. But she’s not alone.

Allison Fisher, a former snooker champion turned pool powerhouse, has won over 80 titles in the U.S. Her clinical precision and consistent presence helped reshape how audiences view women in cue sports.

And today? New voices are rising.

“There are more of us than people think,” said April Larson, a top-ranked American player in her twenties, in a 2022 interview with The Billiard News. “But we still walk into some halls and get underestimated. That just makes it sweeter when we run the table.”

Players like Tina Malm, a respected instructor and competitive player, emphasize community:

“We teach each other. Women support women here. That’s what keeps the game alive,” said Tina Malm in Billiards Digest in 2021.

Social media has also changed the landscape. Players like Masako Katsura and Margaret Fefilova have built international followings, proving that skill travels faster than stereotype.

But there’s still work to be done. Visibility, sponsorship, respect—these are battles still unfolding.

Passing the Cue

The digital age poses a big question: who’s next?

Veterans pass on tips in bar leagues and on YouTube. TikTokers break down trick shots. Reddit forums argue over chalk brands. Mentorship happens in comments, not just smoky rooms. But with fewer halls and shrinking cultural space, the game’s future feels delicate.

A Game on the Edge, Still Holding On

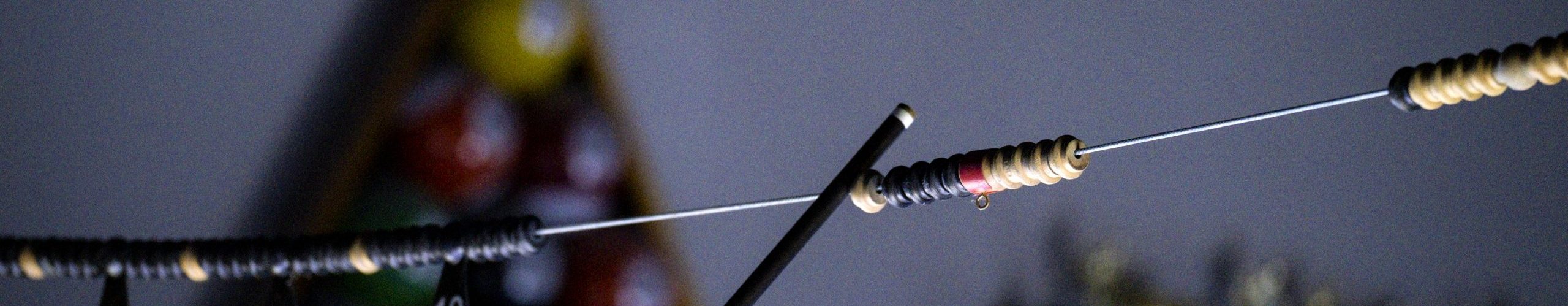

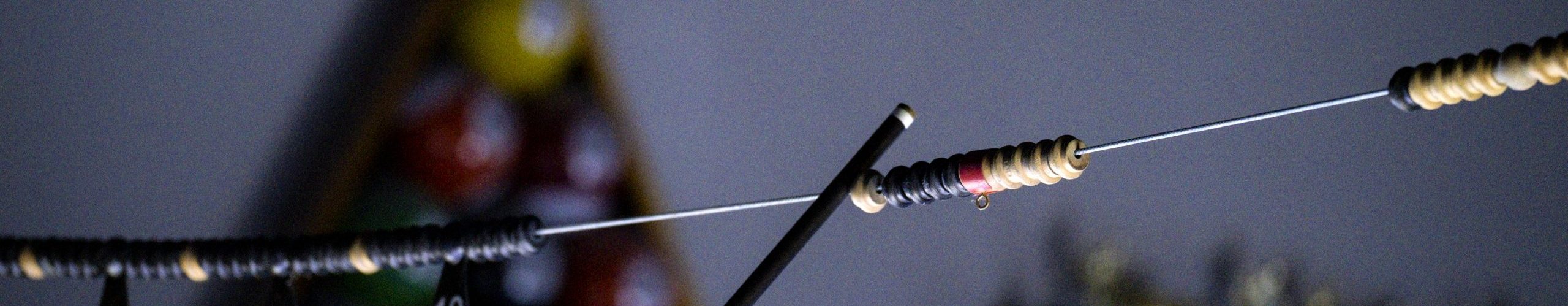

Pool – A Game on the Wire isn’t just history—it’s a love letter. A study in geometry, grit, and grace.

The title itself is layered. Old halls tracked scores with beads on a suspended wire. “On the wire” also refers to handicapping a match. And pool in America? Maybe it’s been playing with a handicap all along—struggling for visibility, respect, and stability.

But still it clings. Suspended. Tense. Alive.

The beads are still sliding.

The game lives on.

Pete Marovich is a documentary photojournalist based in the Washington, DC, Metro area. His clients include The New York Times, The Washington Post, Getty Images, European PressPhoto Agency and United Press International.

His photography is contained in the permanent collections of the Smithsonian Museum of American History and the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. He is the founder of the photojournalism collective, American Reportage.